As part of my Celebration of Food Week, I ask you, dear readers: If you enjoy my story below, please think about those who are finding it extremely difficult to buy food right now. I ask you to please consider donating to your favorite hunger-related charity.***

Six years ago was my last summer in Berlin, where I was studying at the Free University. Berlin was the center of my world for a number of years and for various reasons. One reason it was so special was because of the life lessons I learned there...and this is one of the best.

Berlin, generally speaking, can be a gray and rainy place. The first ten days or so of August 2002, while I was writing my Master's thesis, were no exception, filled with downpours and gloom. But then, around this time in the month, the skies cleared, the sun took center stage, and it became hot and balmy.

I was living in a dorm complex, as I had been the last few years, with a mix of friends, old and new, from countries all over the globe: India, Georgia, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Ireland, Spain, China, Pakistan, and many more. My two closest friends were Tanja from Germany and Ivana from Serbia. Ivana was back home that month, and many of our other close friends were away, so Tanja and I banded together for our evening meals.

Dorms in Germany differ greatly from those in the US. Students of all ages (my floor had an age range of about 18 to 34) live together with a shared full kitchen, common room, and bathrooms. Often, people live in the same room for years, as I did. Cafeterias are located at the universities, but often student housing, like ours, is not. As a result, we had no meal options in our dorm except for the food that we ourselves shopped for and cooked.

Nightly meal preparation had been a highlight of my time there since the beginning. Through cooking, I learned more about other countries' tastes and customs. And we had had all manner of multicultural potluck dinner parties with the residents on the floor.

But this time in August was different. My evenings with Tanja were effectively a master class on the philosophy and technique of cooking as a way of life.

Tanja is an excellent cook. Somehow, whatever she puts her hands to turns into a delicious dish. Tanja is also a very spiritual person, someone who likes to search for meaning and beauty in all that she does. We cooked dinner together every night that hot part of August, and it became ritual.

As students, naturally we did not have a lot of money. However, what Tanja helped me to discover was that it's not just what you prepare, but how you prepare it. Quality was paramount: Buy the best that you can afford.

Even if it meant having a simpler meal, we bought Barilla pasta and fresh tomatoes, almost bursting at the seams. I splurged on a small piece of Parmegiano Reggiano, and we would always have a bottle of Rioja or Navarra. (I'll never forget the lesson I learned from a Spanish floormate early on: "Always buy Spanish wine; it's the best you can get here for a low price.")

The dinner ritual began earlier in the day, when we would phone each other about what we wanted to do for our meal. We would each then shop for ingredients to bring that evening. I would go to the supermarket, examine the vegetables and look for the most beautiful and fragrant specimens. They were the raw materials for a work of art, and I laid them out carefully in my shopping basket. Bunches of arugula, large white mushrooms, single carrots. I would look for surprises, like a thin bar of dark Belgian chocolate -- the brand most Belgians actually buy, as I had learned from a friend from that country. For the rest of the day, I would think about how we would transform this into our feast.

When evening came, I would bring my bag of bounty with me to Tanja. We would talk and laugh as we prepared the food and Tanja instructed me on how to slice and how to season. One night it was the pasta with fresh tomatoes, just a bit of fresh basil and Parmesan shredded on top. "Frischer geht's nicht," said Tanja -- "It doesn't get any fresher than this!"

My room had a balcony that looked onto the river. But more often we cooked in Tanja's kitchen. She was living in another building in the dorm complex -- a high-rise -- and she was on the 10th floor. We would eat dinner on her balcony and watch the sun set and planes take off and land at Tegel Airport in the distance.

I wondered each day how long the fine weather would last, and each day it continued, into the beginning of September. It was as if even the atmosphere was saying this was an important time in my life: Pay attention! I got used to our tradition of "das heilige Essen," food that was so conscientiously prepared that it really felt sacred, feeding both our bodies and spirits.

Food was no longer a commodity. Every ingredient was precious.

I have found no photographs of our dinners that August, so I must rely on my memories. The specifics of every evening have naturally grown fuzzy, and I am left with a melange of images, words, and sensations from those weeks.

Even though I am far away from those glorious last days of student-hood, and even though I often find myself cooking something frozen after work (if I cook at all), when I do set out to prepare a meal with every ounce of myself, I think of Tanja and that August.

"Einfach das Beste" or "Simply the best," as Tanja said. That is what food can be, if your approach is right. It can be a celebration of life, of the earth, of whatever money you have to create a work of art and a way of living.

***

If you enjoyed my story, please think about those who are finding it extremely difficult to buy food right now. I ask you to please consider donating to your favorite hunger-related charity. Let me know what you think!

Thank you, Tanja, for your friendship and your inspiration. And thank you, Michael, for helping edit this piece.

There's me out in nature!!! So refreshing for a city girl like myself. Even though it was only for a few hours, it definitely helped recharge my batteries.

There's me out in nature!!! So refreshing for a city girl like myself. Even though it was only for a few hours, it definitely helped recharge my batteries.

During his two-week rest and recuperation leave while serving a 15-month deployment in Iraq, Roy and his parents volunteered their time preparing and serving meals at a soup kitchen and shelter near their home in New Hampshire. He also donated $1,000 to the soup kitchen and convinced a large corporation to match his contribution.

During his two-week rest and recuperation leave while serving a 15-month deployment in Iraq, Roy and his parents volunteered their time preparing and serving meals at a soup kitchen and shelter near their home in New Hampshire. He also donated $1,000 to the soup kitchen and convinced a large corporation to match his contribution.

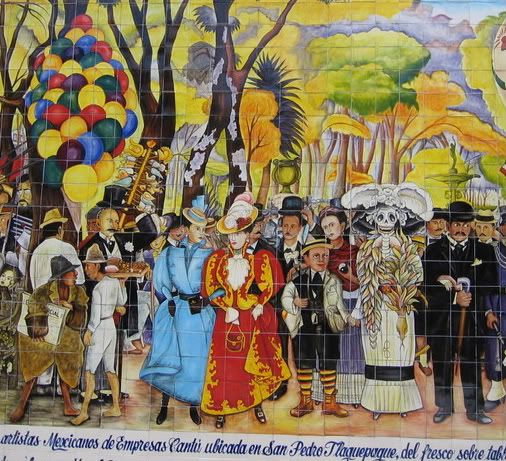

A relaxing lunch at Casa Fuerte in Tlaquepaque, Mexico with some of the great fellow travelers I met.

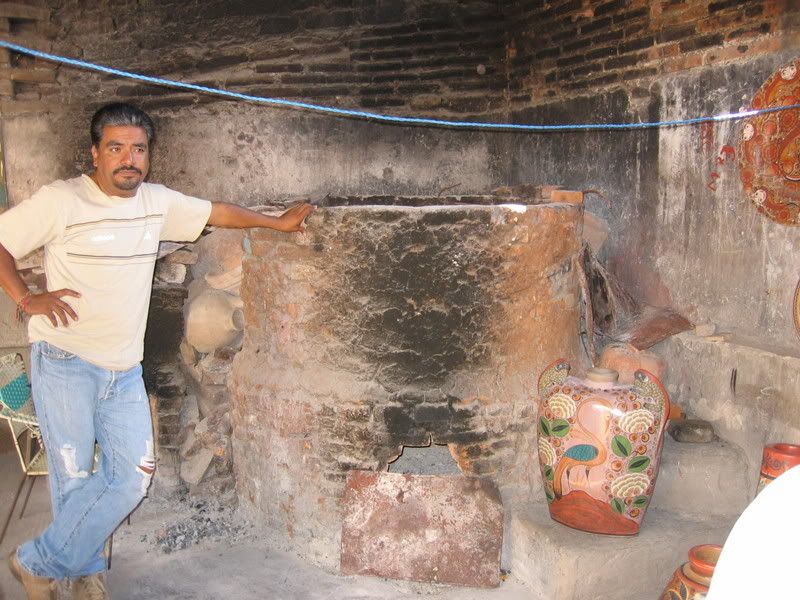

A relaxing lunch at Casa Fuerte in Tlaquepaque, Mexico with some of the great fellow travelers I met. Vasquez son by his family's kiln and handmade vase - part of the artist studio tour in Tonala.

Vasquez son by his family's kiln and handmade vase - part of the artist studio tour in Tonala.